Abstract

All business love to measure and simplify complex aspects of business into mere numbers. This allows business to identify leaders in their fields and benchmark their own performance. The approach to sustainability by many organisations has been no different. There is constant drive to simplify complex issues into a set of numbers. How we choose to measure sustainability is just as important as the measuring itself. Using the wrong tools to measure sustainability will poorly identify leaders to benchmark and follow.

Introduction

This paper explores the language of content utilised in RobecoSAM methodologies and organisational sustainability disclosure survey’s. This language will be assessed against the four conceptions of sustainability: rethinking, reinventing, relating and responding (Kurucz, Colber, & Wheeler, 2013). The purpose of this paper will be to identify strengths and weaknesses of the methodology and frameworks used to identify sustainable organisations. A weakness will be seen as appearing to enhance reductive thinking (Kurucz, et al, 2013) and focus on mitigating impacts, trade-offs and australian pokies online social responsibility projects apart from the core business. Strengths will be seen as an integrative approach (Kurucz, et al, 2013) and seek to identify and promote organisations that seek the true triple bottom line, adapting the organisations and moving sustainability into the core of the business. This is important because organisations such as Exxaro Resources, UPS and the Canadian National Railway Co are identified by RobecoSAM as sustainable organisations largely based upon the organisations responses. The organisations are then promoted as highly sustainable investments to investors. This could be detrimental to the long term investor if in fact the organisations are simply posing as sustainable organisations where it is business as usual and they are actually just focusing on managing risks and mitigating impacts.

This paper will firstly give some background to corporate sustainability reporting and its history. It will then identify some key studies that link voluntary sustainability activities and reporting to important financial indicators such as return on assets, stock price, total revenues and net profit. Thirdly this paper will introduce Kurucz, et al, (2013) model for embedding sustainability within an organisation through reconstructing value and its four constructs. This strategic framework will be applied to analyse the RobecoSAM methodology identifying strengths and weaknesses drawing a conclusion as to whether it may score organisations that take a reductive or an integrative view of sustainability higher.

Background

Climate change is potentially the most challenging problem facing humankind largely because it is the key link to so many problems; global debt, energy security, food shortages and ecological degradation can be all linked to the phenomenon of climate change (Morecroft & Cowan, 2010). The poorest of the planet reside in the most vulnerable of areas they are affected the hardest by climate change and will no doubt have inadequate financial and technical resources to deal with the consequences. Addressing climate change will ultimately involve real engagement with how we view the relationship with the environment, how we relate to fellow humans and thus the threat of climate change will compel humanity to deal with other compelling global issues (Laukkonen, Blanco & Lenhart, 2009).

In order for corporations to account for these global pressing issues; many have turned to sustainability reporting. Corporate sustainability reporting (CSR) evolved in the mid 1990’s as a means for organisations to balance their productive needs with the needs of the environment and surrounding communities. Subsequently, it has progressed as a result of economic growth, environmental regulation (Christofi, Christofi, & Sisaye, 2012) including increased accountability pressures calling for greater organisational transparency (Kolk & Pinkse, 2006). A recent survey of 3300 businesses in 44 countries identified that 31% of these businesses now issue CSR reports either in their financial reports or as separate documents up from 25% two years earlier. Significantly reporting is as its highest level in India (69%), Vietnam (64%), the Netherlands (64%) the Philippines (60%) and Mexico (52%). Conversely, Estonia (6%), Poland (12%), New Zealand (16%) Finland (18%) and Australia (19%) are countries with the lowest number of businesses reporting (Kilcarr, 2013).

The purpose of sustainability reporting is to inform shareholders that an organisation is growing in a sustainable manner. A recent study by Lourenço, Callen, Branco, & Curto, (2014) indicated that accounting measures alone are not representative of an organisations value to investors. A reputation for sustainability influences stakeholder perception in a way that increases cash flows and therefore value (Robinson, Kleffner, & Bertels, 2011). This positive relationship between firm value and sustainability activity and reporting has been the topic of many research studies. These studies indicate that sustainability reporting has a positive influence on net profit and return of assets (ROA) (Ngwakwa, 2009; Lys, Naughton & Wang, 2012; Ameer & Othman, 2012; Eccles, Ioannou &Serafeim, 2012 and N. Burhan & Rahmanti, 2012.); Stock returns and share price (SAM and Robeco, 2011; de Klerk and de Villiers, 2012 & Schadewitz & Niskala, 2010); Revenue growth, estimated vs actual earnings and corporate reputation ( Greenwald, 2012; Bayound, Kavanagh & Slaughter, 2012 and Ameer & Othman, 2012). Although the majority of research points to a positive relationship some studies indicate no significant relationship (Adams, Thornton & Sepehri, 2012; Venanzi, 2012 and Zeigler Rennings & Schroder, 2002) or even a negative relationship (Lopez, Garcia & Rodriguez, 2007 and Detre & Gunderson, 2011). Cormier, Ledouz and Magnan, (2009) suggest that a negative relationship is due to the potential costs and threats associated with sustainability reporting. This would include the over disclosure of information related to research and development, product & process innovation, approaches to risk management, eco-efficiency and training & development.

Reconstructing Value

The majority of the problem the world faces today lie with multinational corporations using outdated methods of value creation. These organisations view value creation narrowly, optimising for short term financial gains while ignoring the true needs of their customers and the long term implications of their actions and inactions (Porter & Kramer, 2011). These organisations take a reductive view of sustainability the focus of their sustainability activities is on social responsibility projects and eco efficiencies or mitigation of power, water and waste. These projects have very little to do with the businesses core strategy and are viewed as risk management or as a socially responsible addition to the business. As the complexities and urgency of climate change become ever more evident there becomes a pressing need to truly challenge the traditional concepts of value creation. True value creation must embed sustainability within an organisations strategy transforming the view of human, social and natural systems. Therefore an organisation that is striving to become sustainable must be reviewing how the organisation at its core creates value by challenging its own assumptions of how the business operates. In order to challenge the paradigms of traditional value creation Kurucz, Colbert & Wheeler, (2013) suggest the following model:

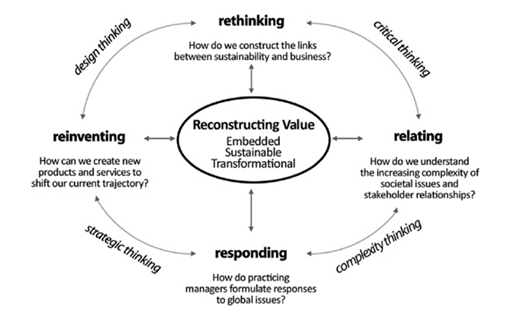

Figure 1.0 Reconstructing value (Kurucz, et al, 2013)

This model represents four constructs of value reconstruction: rethinking, reinventing, relating and responding. These phases are emphasised by four types of thinking: design thinking, critical thinking, complexity thinking and strategic thinking. This model for the process of reconstructing value will provide the strategic framework for the analysis of RobecoSAM’s methodology in identifying a sustainable organisation. It will be used because this model seeks to determine how an organisation considers sustainability. It separates organisations that are focused on mitigating sustainable issues and managing risks from those that are striving integrate sustainability at their core to truly be considered sustainable organisations.

Analysis

RobecoSAM is a sustainability investment specialist. The organisation creates investment portfolios based upon the organisations own methodologies. These methodologies use publicly available information such as CSR reports and a sustainability assessment questionnaire to rank responding organisations by industry. Using this information it ranks these organisations and awards leading organisations in each industry with a gold star announcing it as the sustainability leader for that industry. RobecoSAM justifies its methodology because of the number of studies linking corporate sustainability to positive financial returns in particular stock price and market value. The purpose of this analysis is to critique this methodology and identify key strengths and weaknesses.

Framework & Methodology Strengths

Sustainability is a wicked problem it consists of vast number of interrelated complex issues that have little or no agreement as to causes or solutions. Relating is the ability for an organisation to consider all these different connections and the kind of connections that occur between us and others across geographic locations, human activity and natural context, or business and its stakeholders (Kurucz, et al, 2013). Sustainable organisations will have the ability to consider the complexities of a variety of stakeholders at various times and distances from the organisation.

It is clear that RobecoSAM’s methodology recognises organisations such as UPS and Canadian rail that have the ability to consider stakeholders on multiple levels. RobecoSAM’s methodology rewards organisations that can show concern for stakeholders directly linked to the organisation, from wider stakeholder communities and networks, to society as a whole considering global sustainability issues such as food, water, energy and climate change. For example, UPS collaborates across the globe helping to provide humanitarian relief, tackling malnutrition, engaging in forestry and conservation initiatives, supporting a number of conservation foundations and, from a business perspective, seeking engagement with stakeholders internal and external to its organisation and a collection of government and non-government organisations.

For the investor, the strength of this methodology is that it recognises organisations that have the ability to consider the complexity of a wide group of stakeholders. Being able to consider these complex connections raises the possibility of creating long term sustainable value creation in terms of products and services. These products and services are therefore more likely to integrate the needs of stakeholders in contrast to simply managing the needs of stakeholders.

Framework & Methodology Weaknesses

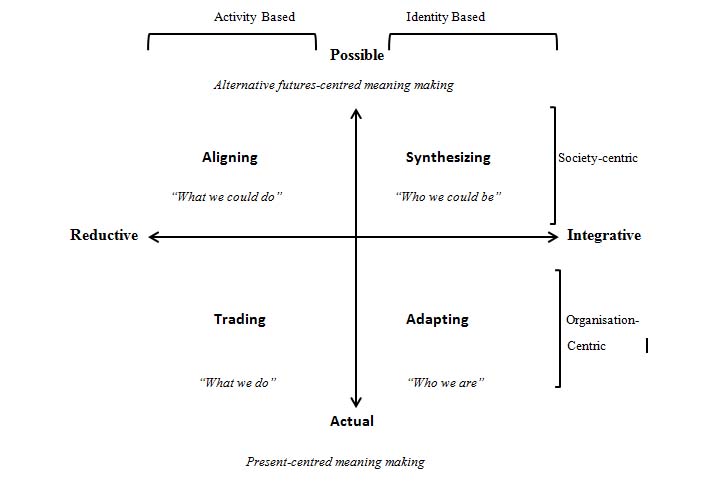

Responding relates to how practicing managers formulate strategies in response to global issues. In the process of reconstructing value how the organisation is perceived is an important factor in unleashing creative strategic potential. Through the greater understanding of strengths and weaknesses, organisations can work towards advancing sustainable visions and better embedding sustainability within strategy (Kurucz, et al, 2013). Reinventing involves designing new forms of relationships that transform the current paradigm of a product or service. It produces novel outcomes that change traditional views and behaviour allowing us to better understand the reconstruction of value (Kurucz, et al, 2013). These two dynamics relate in that how an organisation’s managers view and perceive sustainability will influence the decisions and solutions of how they resolve the problem. Kurucz, et al, (2013) suggest in the following figure 2.0 that there are four conceptions of how an organisation may view sustainability.

Figure 2.0 The four conceptions of sustainability (Kurucz, et al, 2013)

From RobecoSAM’s questionnaire it is clear that it seeks to identify organisations that identify and deal with stakeholders at the individual level. These organisations seek to “balance” sustainability issues or make trade-offs between different stakeholders and the businesses activities. The questionnaire is also fixated on past and current performance levels. It seeks clearly defined measures and targets related to current political structures, relationships, markets, operations, products/services, capabilities and cultural traditions. Kurucz, et al, (2013) would see this as an organisation fixated on a “Trading” conception of sustainability. This is characterised by organisations focused on “what we do”, activities are focused on the short term and aimed at meeting the operational plan and maximising organisational or shareholder value. A sustainability framework is seen as a useful tool to manage stakeholders were interactions and trade-offs are seen as unavoidable.

For the investor, a key weakness of this methodology is that RobecoSAM holds what corresponds to a “trading” view of sustainability. Therefore any organisation that is recognised with this methodology will likely hold similar sustainability values. The issue with a fixation on past performance and measures is that it constrains sustainability to an organisation’s current activity. The organisation cannot envision truly unique and sustainable future because it is stuck focusing on what it currently does or did. Those organisations with a trading view do not necessarily dismiss other values but financial values take precedent over all others. This view is reinforced throughout the RobecoSAM questionnaire as there is a constant need for some form of financial link either as a cost-saving or revenue generating aspect.

Rethinking involves questioning the underlying assumptions about our actions in the world. Here an organisation must question the, often unstated, assumptions about how the world works and how we think it works (Kurucz, et al, 2013). Therefore any methodology to identify a sustainable organisation must consider how the organisation currently explores the benefits and limitations of current practices and how it considers the possibilities for change. An organisation seeking sustainable change would be seeking to integrate sustainability into the core of the business by changing the way it fundamentally carries out its business. While an unsustainable organisation would see sustainability as a risk to be managed focusing on running the business as usual with emphasis on social responsibility projects and eco efficiencies apart from the business.

The methodology statement from RobecoSAM, (2013) states that key to its methodology is looking for the:

“Implementation of strategies to manage these sustainability risks or to capitalize on related opportunities in a manner that is consistent with its business model”.

This does not seek organisations that are looking to create new value from innovative approaches but rather it clearly seeks to identify which organisations can best hold the status quo. Organisations that are ranked highly in this regard are more likely taking a trade-off approach. Where an organisation does not challenge the current dynamics of its business but instead does something for the environment, or the economy or for society.

The weakness of this methodology is that it likely rewards organisations that at their core are unsustainable furthermore it recognises them as sustainability leaders. For example Exxaro Resources Ltd, BG Group PLC, and Thai Oil PCL are all in highly extractive unsustainable industries (oil, gas and coal) and all received gold awards and recognition as sustainability leaders. British American Tobacco PLC also received a gold award as a sustainability leader when their product has been proven to be detrimental to human health and the cause of millions of deaths worldwide.

An investor investing in sustainability would likely consider the long term viability of an organisation before investing. It is questionable, in a future with limited resources, as to whether organisations in highly extractive industries or those highly reliant on fossil fuels such as those in the transport and transport infrastructure industry could ever be considered sustainable in their current state. Therefore a sustainable investor would be seeking to invest in organisations that use sustainability to challenge existing business models to capitalise on new and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Conclusion

RobecoSAM’s framework and methodology seeks to identify sustainable organisations for investment as their view is that they will provide better returns to investor in the long run. While studies have shown that this ideology has merit the methodologies used to identify sustainability leaders should be questioned.

The strength of the methodology used is that it identifies organisations that have the ability to engage with a wide number of stakeholders interacting with the organisation at varying levels, distances and times. This is a complex process but organisations that can accomplish it are more likely to be able to create value in terms of products and services that integrate the needs of stakeholders with the needs of the organisation.

However the methodology takes a highly reductive view of sustainability and is fixated on current and past performance that must be linked to financial returns. Thus the types of organisations that are selected as leaders in sustainability reflect these same values. The result is a large number of organisations in highly extractive industries or similarly unsustainable industries named as sustainability leaders. It is not that these organisations do not see value in sustainability but that their focus is on what they can currently do. If their view of sustainability is constrained by what they currently do then a sustainable future cannot be achieved, because the only future possible is one constrained by the organisations current capabilities.

“Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (Brundtland Commission, 1987)

Finally sustainability is a complex problem that will require complex solutions. Benchmarking tools such as RocecoSAM’s methodologies seek to oversimplify the issues of sustainability, and in doing so lose sight of the values associated with sustainable development. Sustainable organisations will be focused on “who they could be” fixated on future possibilities rather than past and present performance. In addition, these organisations will also take an integrative approach to sustainability seeking to align organisational values with stakeholder values, rather than seeking to find a balance between financial returns and social responsibility.

References

Adams, M., Thornton, B., & Sepehri, M. (2012). The impact of the pursuit of sustainability on the financial performance of the firm. Journal of Sustainability and Green Business, 1.

Ameer, R., & Othman, R. (2012). Sustainability Practices and Corporate Financial Performance: A Study Based on the Top Global Corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(1), 61-79.

Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2009). Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 279-288. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9806-0

Bayoud, N. S., Kavanagh, M., & Slaughter, G. (2012). Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Corporate Reputation in Developing Countries: The Case of Libya. Journal of Business and Policy Research, 7(1), 131-60.

Brundtland Commission. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. United Nations.

Christofi, A., Christofi, P., & Sisaye, S. (2012). Corporate sustainability: Historical development and reporting practices. Management Research Review, 35(2), 157-172.

Cormier, D., Ledoux, M. J., & Magan, M. (2009). The Information contribution of social and environmental disclosures for investors. Retrieved http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1327044

de Klerk, M., & de Villiers, C. (2012). The value relevance of corporate responsibility reporting: South African evidence. Meditari Accountancy Research, 20(1).

Detre, J. D., & Gunderson, M. A. (2011). The Triple Bottom Line: What is the Impact on the Returns to Agribusiness?. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 14(4), 165-178

Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). The impact of a corporate culture of sustainability on corporate behavior and performance. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gatti, L., & Seele, P. (2014). Evidence for the prevalence of the sustainability concept in European corporate responsibility reporting. Sustainability Science, 9(1), 89-102.

Greenwald, C. (2010). ESG and Earnings Performance. Thomson Reuters.

Kilcarr, S. (2013). The rise of sustainability reporting in the corporate world. Fleet Owner, Retrieved from http://ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1462852742?accountid=8440

Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. (2006). Stakeholder mismanagement and corporate social responsibility crises. European Management Journal, 24(1), 59-72. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/237034300?accountid=8440

Kurucz, E.C, Colber, B.A, & Wheeler, D. (2013). Reconstructing value: Leadership skills for a sustainable world. Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Laukkonen, J, Blanco, P. K, & Lenhart, J. (2009). Combining climate change adaption and mitigation measures at the local level. Habitat International 33: 287-292

Lopez, M. V., Garcia, A., & Rodriguez, L. (2007). Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 285-300.

Lourenço, I. C., Callen, J. L., Branco, M. C., & Curto, J. D. (2014). The value relevance of reputation for sustainability leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(1), 17-28. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1617-7

Lys, T., Naughton, J., & Wang, C. (2012). Signaling Through Corporate Accountability Reporting. Available at SSRN 2143259.

Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). W(h)ither ecology? the triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 13-29. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8

Moody-Stuart, M. (2006). Discussion of ‘does sustainability reporting improve corporate behaviour?: Wrong question? right time?‘. Accounting and Business Research, , 89-94. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/198183816?accountid=8440

Morecroft, M. & Cowan, C. (2010). Responding to climate change: An essential component of sustainable development in the 21st century. Local Economy 25(3): 170-175

N.Burhan, A. H., & Rahmanti, W. (2012).The Impact of Sustainability Reporting on Company Performance. Journal of Economics, Business, and Accountancy| Ventura, 15(2), 257-272.

Ngwakwe, C. C. (2009). Environmental responsibility and firm performance: evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2), 97-103.

Porter, M. E, & Kramer, M. R,. (2011). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism – and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review 64

Robinson, M., Kleffner, A., & Bertels, S. (2011). Signaling sustainability leadership: Empirical evidence of the value of DJSI membership. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(3), 493-505. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0735-y

RobecoSAM, (2013). Measuring Intangibles: RobecoSAM’s Corporate Sustainability Assessment Methodology. Retrieved http://www.robecosam.com

SAM Research, & Robeco Quantitative Strategies. (2011). SAM White Paper: Alpha from Sustainability. sam sustainability investing. Retrieved from http://www.robecosam.com/images/Alpha_from_Sustainability_e.pdf

Schadewitz, H., & Niskala, M. (2010). Communication via responsibility reporting and its effect on firm value in Finland. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17(2), 96-106.

Van Zyl, A. S. (2013). Sustainability and integrated reporting in the south african corporate sector. The International Business & Economics Research Journal (Online), 12(8), 903-n/a. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1418721316?accountid=8440

Venanzi, D. (2012). Social Ratings and Financial Performance: An Instrumental Approach. Available at SSRN 2188859

Ziegler, A., Rennings, K., & Schroder, M. (2002). The effect of environmental and social performance on the shareholder value of European stock corporations. Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Mannheim. Retrieved from http://www.eea-esem.com/papers/eea-esem/2003/342/paper.pdf.

Recent Comments